Catalyse an Adaptive Leadership System

Overcoming organization extinction requires a new leadership system

Organizations are disappearing at an increasingly alarming rate. This mass extinction is happening because companies can’t evolve quickly enough to keep up with the accelerating rate of change. If organizations can’t adapt they die.

By Prof. Dr. Tony O’ Driscoll, Research Fellow at Duke Corporate Education

Like many species on our planet, organizations are disappearing at an increasingly alarming rate. The World Economic Forum reports that, since the year 2000, just over half of the names of companies on the Fortune 500 have disappeared and Innosight predicts that 75% of S&P 500 companies will be replaced in the next ten years.

This mass extinction is happening because companies can’t evolve quickly enough to keep up with the accelerating rate of change. If organizations can’t adapt they die.

The Complex Reality

Ensuring an organization’s survival in the face of increased uncertainty presents a pernicious paradox for leaders. On the one hand, they must continue to run their core business as efficiently as possible. On the other, they must develop and implement strategies to change their business in response to swift and sweeping ecosystem shifts. Navigating the dynamic tension between running the business and changing the business is a clear and present danger for leaders today.

To efficiently run the business, leaders in hierarchical positions of power maximize the efforts of others through top-down command and control mechanisms. In more stable and predictable times, this was highly productive. Today, however, increasing organization mortality rates signal an urgent need for a different leadership approach.

Business survival requires that senior leaders distribute leadership responsibility, complementing hierarchy and formal authority with an agile collaborative leadership system designed to autonomously sense and respond to business ecosystem shifts. Leaders at every level must embrace what Harvard professor Amy Edmondson calls “Situational Humility,” requiring them to become comfortable with being uncomfortable, show vulnerability, seek help, solicit feedback, dispense mandates less and ask questions more.

This conception of leadership is not new. In 1924, social worker and management consultant Mary Parker Follet observed that: “Leadership is not defined by the exercise of power, but by the capacity to increase the sense of power among those led.” Follett’s “Law of Situation” emphasized that “orders should not be given from one person to the other. Instead the order giver and the order taker should take the order from the situation rather than the authority of the individual.” This perspective means that the leader in any given situation is determined by the context, not by the individual’s position.

Peter Drucker argued that “Without followers there can be no leaders.” Harvard professor Barbara Kellerman envisions leadership as a “system that consists of three parts, each of which is equally important and each of which impinges equally on the other two: The leader, the follower and the context.” Red Hat chief executive Jim Whitehurst believes that “Your job as a leader is to create the context for people to do their best work.”

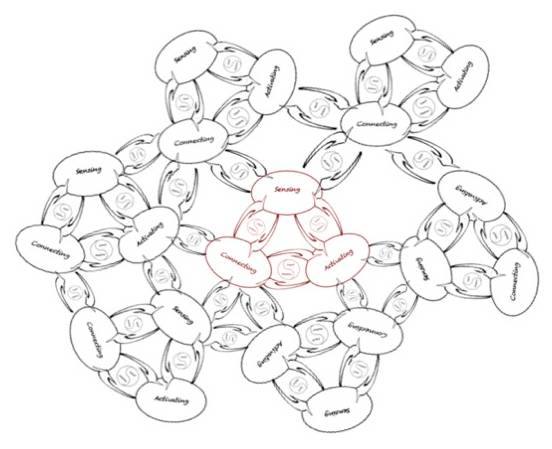

These perspectives underscore how leadership can be described as a complex and dynamic set of leader-follower interactions that is a property of a system not of an individual. In complex and changing contexts, leadership is exercised as a process of social influence to maximize the efforts of others towards the achievement of a shared goal. In this system of leadership, hierarchical command-and-control gives way to networked connection-and-collaboration where leadership and followership roles are far more fluid and context-dependent.

In stable and predictable “run the business” operating contexts, the leader’s job is to make decisions and the follower’s job is to execute them. In changeable and complex “change the business” operating contexts, leadership and followership roles ebb and flow within a fluid network-like structure that responds dynamically to contextual shifts. The adoption of either a leadership or followership role within this adaptive leadership system is neither assigned hierarchically nor assumed individually. Rather, it emerges organically based on the context within which agency is being exercised.

This is a complex adaptive property called emergence: self-organization in the absence of hierarchical control.

The Adaptive Systems Approach to Leadership

MIT’s Peter Senge argues that we need a new kind of leader – an adaptive systems leader – to catalyse the collaborative leadership required to successfully navigate dynamic, complex and systemic change. Stanford Professor Kathleen Eisenhardt’s research reveals that an adaptive systems approach to leadership creates the conditions within which complex behaviour emerges,3 resulting in the ability of the organization to co-evolve with its environment.

The value of adopting an adaptive systems approach to leadership is clear. Deloitte research shows organizations that focus on building systemic level leadership capabilities attain 37% higher revenue per employee, 9% higher gross profit margin and they are five times more likely to be effective at anticipating and responding to change.

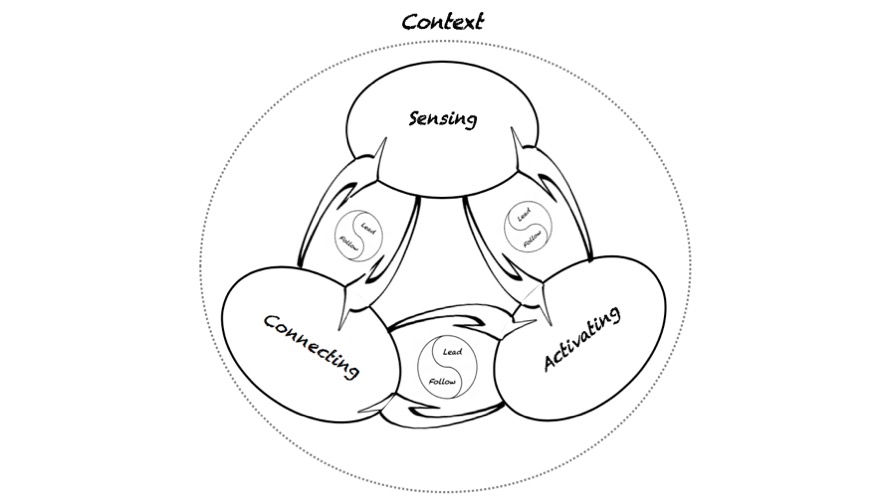

The nucleus of such an adaptive leadership system is comprised of three interconnected activities (see Figure 1):

- Sensing involves monitoring external and internal environments to recognize patterns, applying varying perspectives and identifying potential progression-paths to respond to business ecosystem shifts

- Connecting involves creating the contextual conditions required to encourage constellations of capability to coalesce around these progression-paths

- Activating involves engaging in rapid cycles of experimentation, learning and adaptation to reveal optimal progression-paths, and following through on their execution.

Within this adaptive system, the role of leadership is not to control but to catalyze. The bonds between each of these activities are catalyzed by emergent leadership-follower interactions. Adaptive leadership systems can be characterized as tightly coupled, open and transparent feedback loops between leaders and followers that constantly monitor their shifting business context and allow autonomous agency to coalesce around these shifts. (See Figure 2)

Catalysing an Adaptive Leadership System

Today, the interdependencies between strategy design and delivery are far more fluid and dynamic than ever before. Strategy design and execution are no longer discrete problems to be solved at the top and bottom of a rigid leadership hierarchy. Instead, they are emergent polarities that must be navigated by means of a leadership system that fosters followership, experimentation, learning and adaptation.

Catalyzing such an adaptive leadership system requires a fundamental paradigm shift from leaders in what they believe about what it means to lead. The first step in building an adaptive system will require unlearning. System leadership is not about exercising control, but increasing connections. It is not about enforcing rules but encouraging agency. It is not about exerting power over others but generating energy among others. It is not about taking individual responsibility but cultivating organization response-ability.

Systems leadership is fundamentally different and increasingly important organization capability. As a leader, are you ready to do what it takes to build an adaptive leadership system within your organization?

This article was originally published at Dialogue Review

This research was supported by the Brightline Initiative and carried out by Dr. Tony O’ Driscoll at Duke Corporate Education.